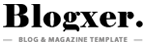

Not merely an outlet for Katie Holmes to scout future exes, “Collateral” (2004) is an expert portrayal of strong and weak personalities interacting, and the weaker personality believably changing over the course of one night. Although the plot of Vincent (Tom Cruise) checking contract kills off his list with the unwitting help of cab driver Max (Jamie Foxx) is an excuse to explore personalities, win Oscars (in the case of Foxx) and unleash one-liners, Stuart Beattie pens a believable script, smartly utilizing his one allowed bit of coincidence.

Trusting his elite cast, director Michael Mann knows how to let things flow within scenes of this engrossing 2-hour film. Max is driving lawyer Annie (Jada Pinkett Smith) from the airport to downtown, and the conversation is natural between two charismatic but cautious people, keeping it professional. We catch the undercurrents that there might be attraction there, but they are from different walks of life.

Before that, there’s a brief moment when Max shuts his cab door and simply sits, temporarily free from the world’s noise. From the very beginning, Mann makes this movie intimate.

“Collateral” (2004)

Director: Michael Mann

Writer: Stuart Beattie

Stars: Tom Cruise, Jamie Foxx, Jada Pinkett Smith

Degrees of separation

Beattie and Mann allow us to get to know and like Max – who insists his 12 years as a cabbie mark a “temporary job” – and then we react to Vincent through his eyes; the Everyman and the movie viewer teaming up to get a psychological handle on this interloper. Cruise appropriately plays a cool movie villain, but Vincent has stepped into an established realistic context.

As such, the crime-movie rules might not always apply in “Collateral.” Of course this night of Vincent’s six contract kills will end with him killing (or at least intending to kill) Max as collateral damage, right? Well, maybe I’m naïve, but I thought “Possibly not.” At least I never knew how the story would end. Seeing how Max’s boss treats him, I wondered if Max might ask for a permanent gig as Vincent’s driver.

Mann puts us in a world of immediacy, not one where Max has time to get philosophical about right and wrong. Yet “Collateral” is a think piece about right and wrong, appropriately set in Los Angeles, home to (as Vincent tells us) 17 million people who don’t know each other, a perfect blank slate to project black-and-white questions.

On the surface, we can ask whether the bad guy is killing other bad guys (and therefore it’s fine), but I think the film is interested in the deeper question of whether any of this matters. It’s an emotion-free job to Vincent, and while Max nominally represents the Everyman’s recoil to that, it feels like he’s the only Everyman in this city, like he’s outnumbered. (Refreshingly, Mark Ruffalo’s police detective Fanning briefly challenges that notion.)

The city that always sleeps

I could make a jab about how “Collateral” follows “24” in wrongly portraying L.A. as having smooth traffic flow, but to be fair, the action takes place in the middle of the night, when traffic does thin out. Though it’s not exactly a pro-L.A. movie, Dion Beebe and Paul Cameron do lens the city beautifully (and beautifully ugly, if places call for it), leading up to a climactic showdown in a mostly dark skyscraper with panoramic views behind the combatants.

Mann keeps the reality-artistry balance so finely calibrated that there’s room for a proto-“John Wick” action sequence in a Korean night club. Even after several gunshots ring out, many people are still dancing. A city where no one knows each other can become a city where no one cares about each other, and where ultimately no one cares much about anything. It’s convincingly surreal.

There’s also room for old-fashioned cool quips.

Max: “You killed him?”

Vincent: “No, I shot him. Bullets and the fall killed him.”

It’s fun to watch Max change thanks to Vincent’s almost Stockholm Syndrome influence; I went with it because I fell under his sway too. Vincent asks Max: “Since when was any of this negotiable?” Later, Max uses the same line – which could be a go-to for elementary teachers and parents — to enhance his own upper hand on someone else.

Like Miles Davis playing jazz (as evoked by one of Vincent’s conversations with a target), Mann takes the very well-known format of a quip-laden action thriller and infuses it with higher art. In doing so, he doesn’t lose the cool.